I hosted a group of IoD Chartered Directors last week – just by chance, representative of private, public and health sectors (although, all white male, on this occasion – something that needs to be dealt with) – where we talked about the need for effective governance of organisations, now more than ever.

Currently an additional 8m or so people are on the Government’s payroll through the furlough scheme.

The new Future Fund will lead to a number of government stakes in small businesses.

If there is significant default on the more than £1bn of CBILS debt, will there be a wave of government taking even more stakes in private enterprises?

We are entering an environment with quite likely a very different public/private sector balance and perhaps a different public perception of purpose over profit.

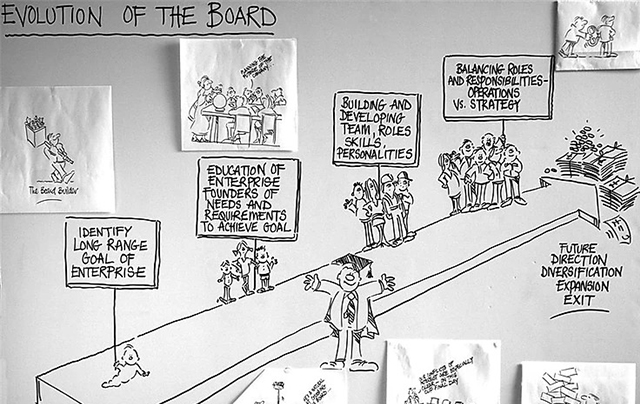

How does corporate governance need to change in such a world? Is this an opportunity for more, and more diverse skills in the boardroom? Are new corporate governance standards required? Should adherence to corporate governance standards be mandatory?

It is clear for the above reasons, and all the other changing dynamics and realisations that are emerging, that we need, as an economy, to up our game. Businesses – be they for-profit or not-for-profit – have a responsibility to their stakeholders more than ever before.

For privately owned business, while the Companies Act 2006 codifies the responsibility of directors to act in the interests of all their stakeholders (not just shareholders), there is increasingly an economic imperative to have the skills around the board table (or board video) that can both adapt to the very changing environment – from compliance and entrepreneurial perspectives – and consider their responsibility in the local and regional economy. Of course, there should be no compromise there – making an effort to recruit people from different backgrounds and characteristics, developing products and services which meet societal needs over consumer fads and minimising impact on the environment can all lead to higher levels of productivity, creativity and sustained business. If you let them.

With not-for-profit organisations – social enterprises, public sector, charities etc. – is it really any different?

It is imperative therefore that we get governance structures right, that align stakeholder interests – uncovering and articulating the common purpose, if you like. At the very least, minimising wasted time and energy in fighting different agendas or competing where its actually better to complement.

Where risk sits becomes very important.

If we think about services that could be state owned, and perhaps have moved between public and private ownership like the railways, with no obvious ‘silver bullet’ of success in either ownership, all that’s really happening is transferring the risk. Finding the right governance and ownership structures where risk is shared, commonly understood and, above all, managed by a team who have the skills to manage that risk, align with a common purpose and achieve the best outcomes.

Within that comes the right level of freedom to operate. I have seen too many times, shareholders trying to micro-manage a board with the obvious negative outcomes, yet without the right boundaries there is too much risk.

In defining a common purpose for the stakeholders in an organisation, identifying the quid pro quo, if you like, could be helpful. If government is taking stakes in small or large businesses, for example, what should it ask for in return? Productivity improvement, contribution to one or more of the Sustainable Development Goals, or board governance standards (such as having at least one professional qualification on a board – eg. a chartered engineer, accountant or director)? If a stakeholder does make such demands, it is incumbent on them to secure common understanding – aim for the carrot not the stick.

Currently the Government has plenty of legislation in place that it could (but rarely does) police board performance and conformance, but actually does very little (if anything?) to encourage or enable effective business leadership.

If we think about the current economic shock of the Covid pandemic and societal shocks (eg. that institutional racism really hasn’t changed much) we can see how important it is for boards (of directors, trustees, ministers) to have the skills to be able to operate rationally, confidently and, above all, authentically to be able to thrive. Having the humility to acknowledge previous mistakes or deficiencies, being able to transition from short term cash management into longer term recovery – all the while adapting to the evolving needs of society. Having the guts to make bold decisions and change things that may have been sacrosanct in the past. It’s a new world and it’s up to everyone to make it better.

We can now see the value in stress testing boards, not least in being prepared for issues affecting the business outside of the control, or horizon, of the board. How many boards of smaller companies (and, remember, over 99% of UK businesses are small & medium sized – less than 250 employees) do such analyses and tests? Is that a ‘market’ problem or a societal problem if businesses fail because they haven’t been governed properly?

In the context of state ownership, albeit in part, we need careful governance structures that shield enterprises (whether social or profit driven) from short-term political cycles that, however hard politicians try, will always be influenced according to election cycles.

I suggest that revision to the UK Corporate Governance code, formerly known as the Combined Code, needs to happen now to better support the evolution of our socio-economy in light of all of the above. Government should also actively encourage and enable good governance via qualified and diverse boards and invest in the development of new, innovative governance models that create a more resilient socio-economy. B-Corps would be a good place to start.

Locally and regionally, boards of directors and of trustees, should think hard about whether they have the right set of skills and perspectives involved in leading their organisations, however large or small, and that you have the right governance structure that aligns with your stakeholders.